Items

-

Arvid and Anna Lena NilssonPicture of original owners of the Avery land.

-

Avery Land DonatorsCharles, John and Nelson Avery and sister Christina Avery Fell.

-

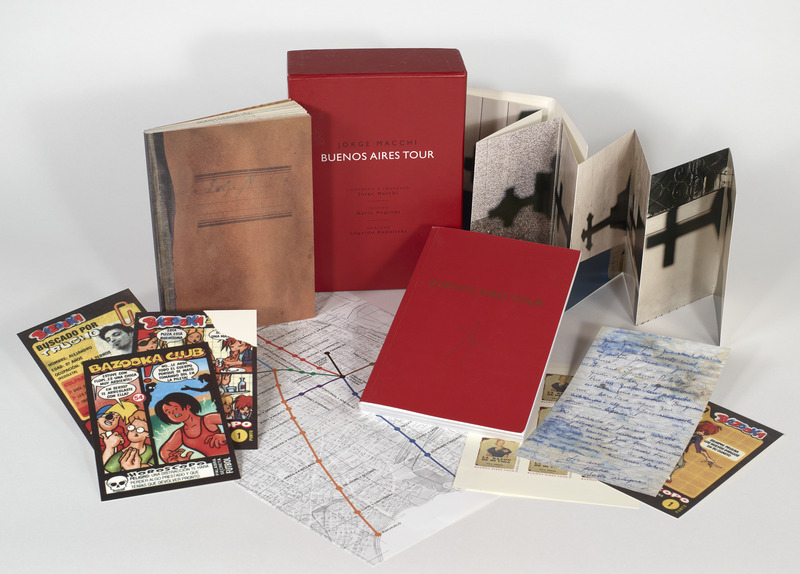

Buenos Aires TourThe arists' book is a box of items related to a tour of Buenos Aires. "Se han editado 1000 ejemplares no numerados y 100 numerados y firmados"--Interior of case. Una guía = A guide -- Un mapa = A map -- Un CD-ROM -- Un diccionario = A dictionary -- Un misal = A mass book -- Una carta = A letter -- Postales = Postcards -- Estampillas = Stamps-- Buenos Aires tour -- Buenos Aires tour, English version.

-

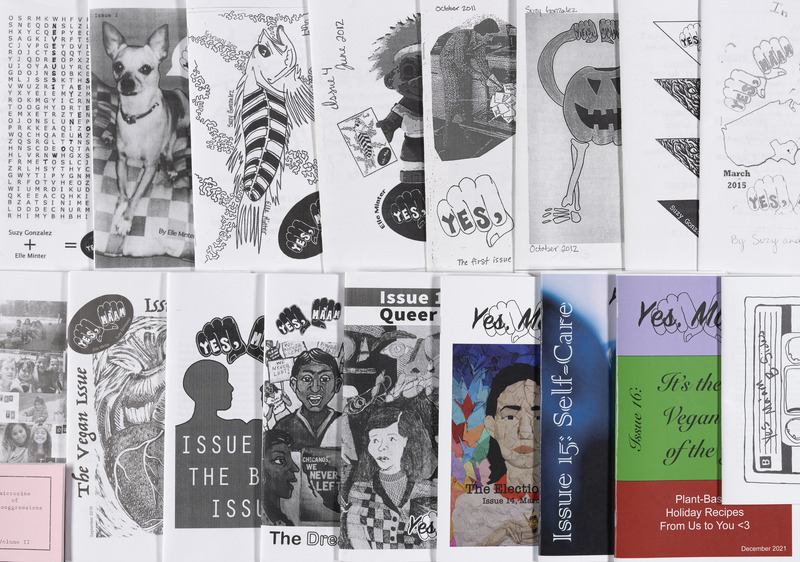

Yes, Ma'amSelf published zine issues by local area artists and Texas State University alumni Suzy González and Elle Minter. Their zines cover feminist issues, social justice issues, animal rights issues, veganism, and more.

-

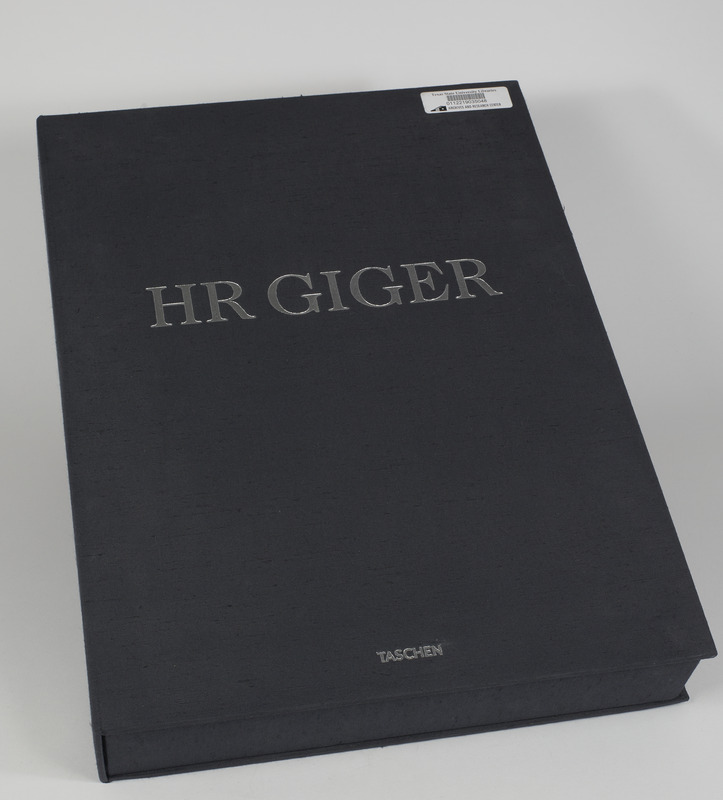

H. R. GigerThis book is copy number 353 in an edition of one thousand two hundred copies and signed by Carmen Giger

-

Artist's booksOriginal art books created by Marc Snyder & other artists, which start as a mixed media image, incorporating drawing, painting, collage, rubber stamps, photographs, and printed text. Then the image is xeroxed onto high quality resume paper, then cut and folded in a very clever way to make an eight page book. These are single-sheet origami or maze books. Some issues are a bit different from the typical "book". For example (2013 [no.2]): On the envelope was a linocut of a howling dog, with "Rex Howls At..." in pencil, with another linocut in the envelope title "The Moon". These books were purchased through the Book of the Month club that the artist offered. They were mailed almost every month.

-

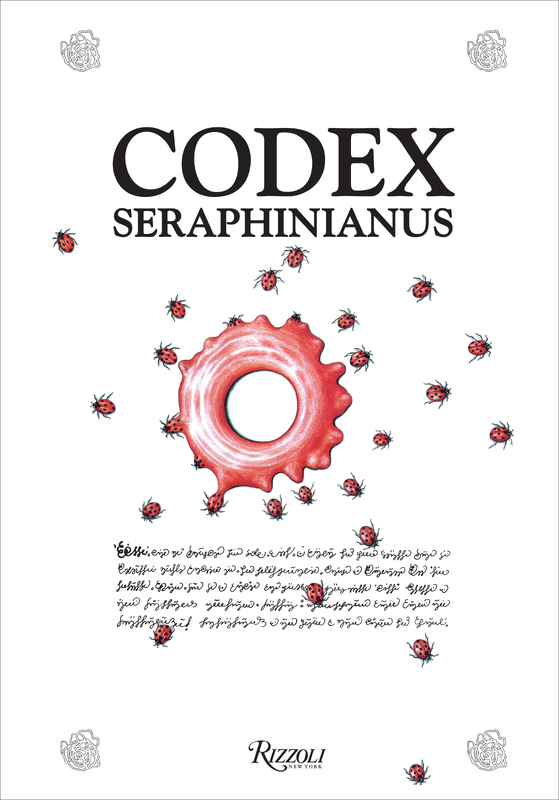

Codex Seraphinianus"An extraordinary and surreal art book, this edition has been redesigned by the author and includes new illustrations. Ever since the Codex Seraphinianus was first published in 1981, the book has been recognized as one of the strangest and most beautiful art books ever made. This visual encyclopedia of an unknown world written in an unknown language has fueled much debate over its meaning. Written for the information age and addressing the import of coding and decoding in genetics, literary criticism, and computer science, the Codex confused, fascinated, and enchanted a generation. While its message may be unclear, its appeal is obvious: it is a most exquisite artifact. Blurring the distinction between art book and art object, this anniversary edition-redesigned by the author and featuring new illustrations-presents this unique work in a new, unparalleled light. With the advent of new media and forms of communication and continuous streams of information, the Codex is now more relevant and timely than ever."-- Publisher's description "This edition of the Codex Seraphinianus, thirty-two years after the first edition published in 1981, has been enriched by yet another original preface by the author"--Colophon Originally published in 1981 by Franco Maria Ricci, Parma, Italy Includes booklet Decodex, in Italian, English, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese and Russian. English translation by Sylvia Adrian Notini Booklet inserted in pocket on page [3] of cover. 1 volume (unpaged) : color illustrations ; 35 cm + 1 booklet (22 pages : color illustrations ; 24 cm)

-

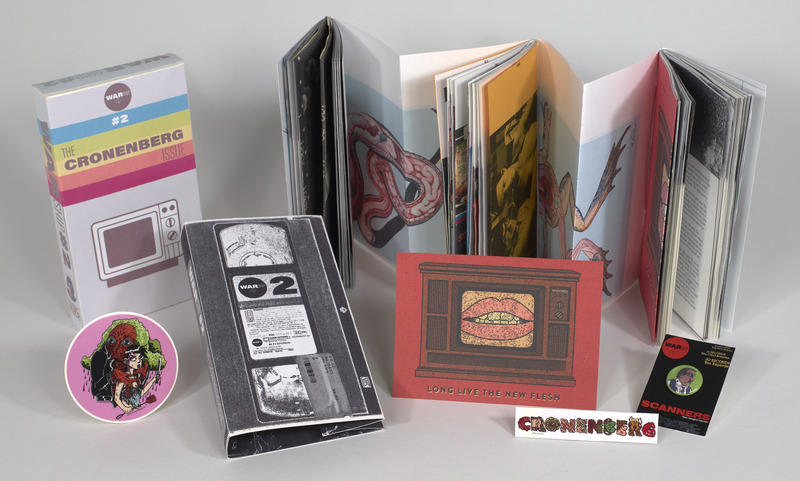

The Cronenberg issueWarship #2 is all about one of our favorite directors, the Barron of gore himself, David Cronenberg. This is a limited edition of 100, 160 pages, and is full of comics, short stories, reviews, drawings, and more! It comes packaged in a VHS box and includes 2 stickers, a button, and a mini print! 1 portfolio (1 zine, 2 stickers, 1 print card, 1 pin button) : illustrations ; in VHS box (19 x 11 x 3 cm).

-

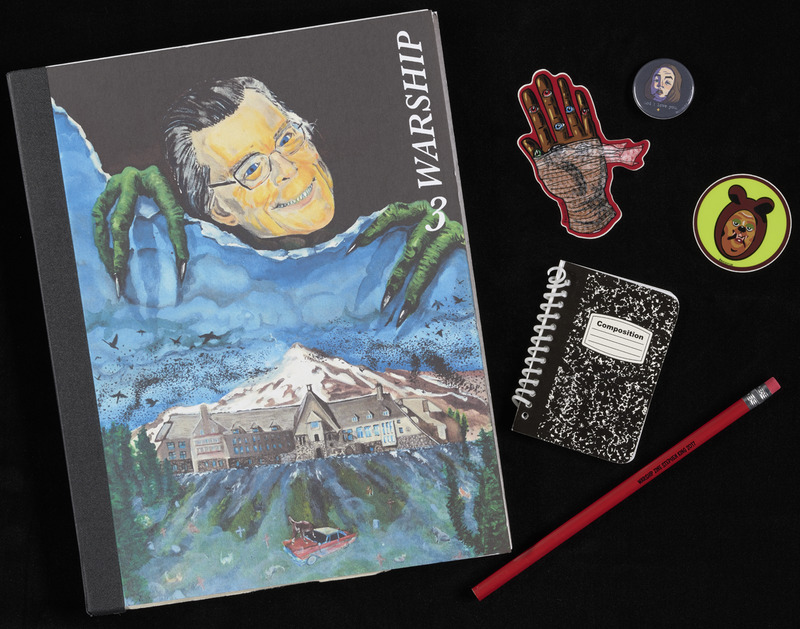

The Stephen King issue1 plastic envelope (1 zine, 1 print, 2 stickers, 1 button, 1 small notebook, 1 pencil) : illustrations ; in envelope (30 x 26 cm) + 1 poster. Title on poster: Stephen King's creepshow

-

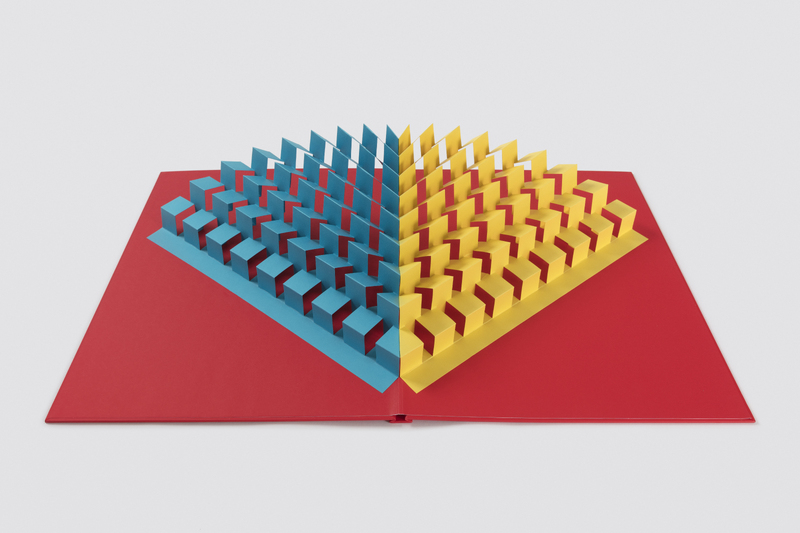

[2,3]"For this special project, Auerbach has created an oversized pop-up book featuring six die-cut paper sculptures that unfold into wonderfully elaborate forms. While much of Auerbach's work has previously dealt with compositions staged in the flux state between 2D and 3D, [2,3] represents an expansion for the artist towards a more sculptural medium. Engineered by the artist, each "page" opens into a beautifully constructed object, intricately conceived so that the large-scale paper works--some up to 18" tall--collapse totally flat when closed. In [2,3], the six sculptures take their cue from a range of geometric forms--the pyramid, sphere, ziggurat, octagonal bipyramid (gem), arc, and möbius-strip. The use of a bright, contrasting palette is familiar from Auerbach's previous work across a range of materials, including acrylics, etchings and C-type prints. By matching intense color to form, [2,3] causes the eye to get lost in the twists and intersections of paper and the viewer finds it difficult to envision how the pages work without animating the book in hand. Bringing together an array of interests, Auerbach has created a groundbreaking project that advances the field of pop-up technology and works as an astonishing stand-alone hybrid book/art-object. Published by Printed Matter, each folio of [2,3] measures 20" x 30" when open. The six volumes will be housed in a specially designed slipcase, and published in an edition of 1,000"--Publisher's Web site. 6 unnumbered volumes : all color illustrations ; 53 x 42 cm + colophon card

-

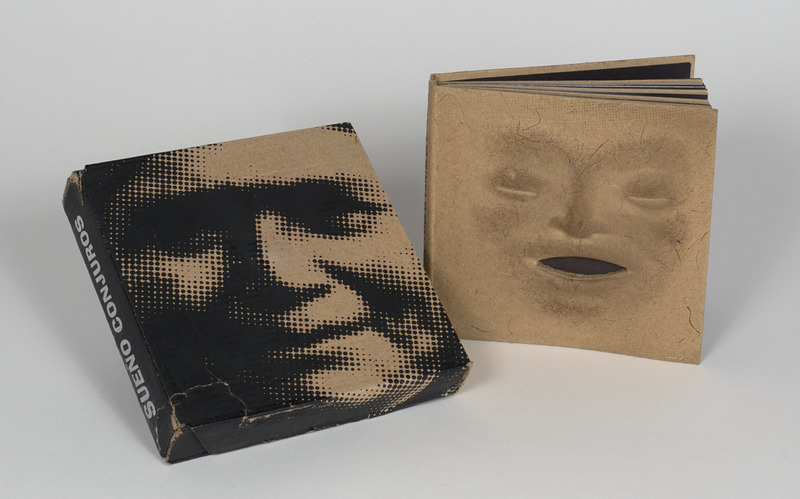

Conjuros y ebriedades : cantos de mujeres mayas"The covers or cover are made of recycled cardboard with corn silk. The interiors are made of recycled paper and everything is silkscreened, that is, sheet by sheet." - From the publisher, Taller Leñateros. Issued in decorated box. The top cover is a face in relief. "Prólogo de la segunda edición: Elena Poniatowska"-Colophon. 11 unnumbered pages, 190 pages : illustrations ; 25 x 26 cm

-

Sueño conjuros desde el vientre de mi madreIn Spanish and Tzotzil "The cover or lining is made of recycled cardboard, with one side embossed. The interiors are made of recycled paper printed using silkscreen and hand-offset printing." - From the publisher, Taller Leñateros. Issued in box 17 x 16 x 4 cm, book has sculptured face on cover. 167 pages : illustrations (some foldout, some color) ; 15 cm + 1 audio disc (61 mins ; digital, 4 3/4 in.) Para convocar a los muertos -- En Bolom Chon -- Un brindis -- Para Evodio -- La muerte de Mario -- La borrachera de la mujer del alférez -- Canto de la mujer borracha -- Anuncio de la fiesta -- Para que la lagartija no coma el frijol -- Para que el murciélago no muerda al borrego -- Contra el arco iris -- Para que no venga el ejército -- Para no tener que robar -- Antsun ti antsun -- Para curar potslom -- Bolom Chon -- La pedida de mano -- Para que el perro no ladre al novio -- Para matar al hombre infiel -- Macho vinik -- Bikitik manvel -- Bolom Chon -- Radio comunidad indígena -- Conjuro para vender pexi cola -- Gracias por darme un hijo -- En el vientre de mi madre sueño conjuros -- Aprendiendo a canta el Bolom Chon -- Canto de la pastorcita -- Soy mujer mi mujer -- La niña tejedora -- Antsot ti antsot.

-

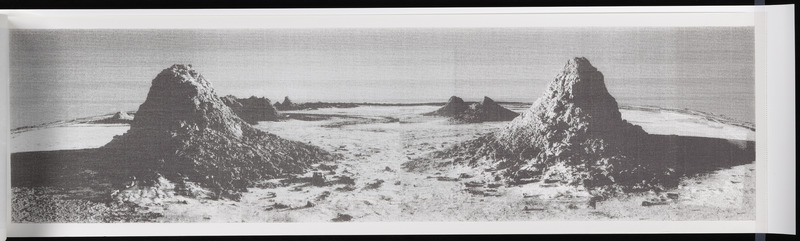

TransmissionNine panoramic thermal prints (31.5 x 8.75 inches) made by the artist. Synthetic paper wrap printed with UV ink. Japanese clip binding. Presented in a cardboard tube.;"Limited Edition of 350.";"Transmission is a communication from our future to our recent past. A warning that if we dont stop stripping our home bare and consuming it to death we will bring about our own extinction."

-

PrimevalLibrary's copy 1 (Special Collect): No. 10 of 20 copies. Purchased. In container with lift-out tray.;" A book in the shape of a tetrahedron is pretty close to the general shape of a volcano. Primeval could be showcasing the earth millions of years ago, but is actually showing the current landscape. With a brief description of what happened in the massive 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens and overhead photos of the newly reformed landscape, in the aftermath of an earth changing event. Primeval unfolds to 4 panels, 3 foldouts, lots of photos, text about the eruption of Mt St Helens, a colophon, and a sampling of real ash from the volcano, bound with wire edge binding. The book is 5.5 x 6 x 6 . Comes with a tetrahedron case. Edition of 20 --From publisher's web site.";"Deluxe, gray case has black bands in center of each side. Title print on each band. Case material is mildly abrasive.";"Includes color illustrations, descriptive and historical text, a capsule of ash from the eruption, and a description of publication production information."

-

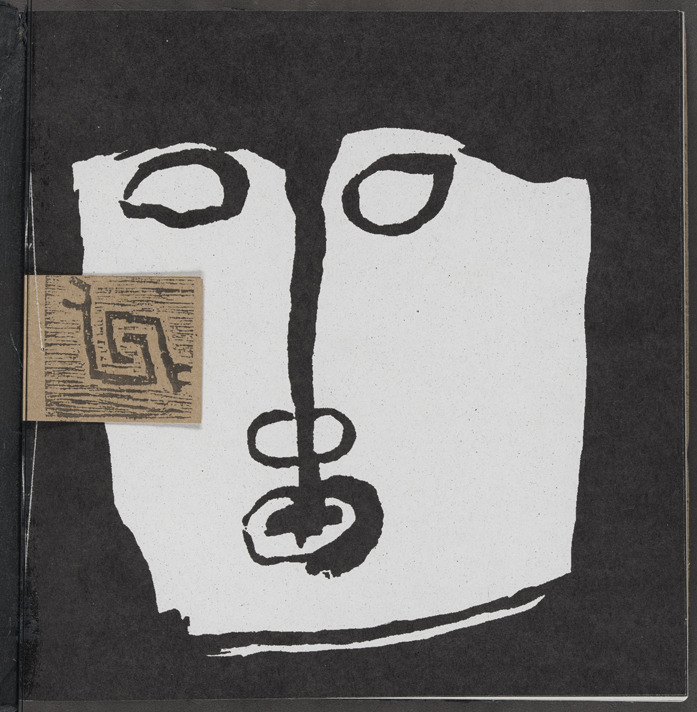

Bolom chonIllustrated and printed in woodblock prints and silk-screens by contemporary Mayan artists a pop-up jaguar in the center fold. "The cover or lining is made of recycled cardboard with corn silk in low relief. The endpapers are made of maguey fiber paper. The interiors are made of recycled paper and are all silkscreened, sheet by sheet. The jaguar's whiskers are made of maguey fiber. The entire book is handmade." - From the publisher, Taller Leñateros. Book design, typesetting, page numbers [by] Ambar Past and Sara Miranda. Recording the CD [by] Ámbar Past [and others].;"Includes a CD audio of several versions of the song, Bolom chon, tucked into a pocket at the back of the book.";"An edition of 99 copies, numbered and signed."

-

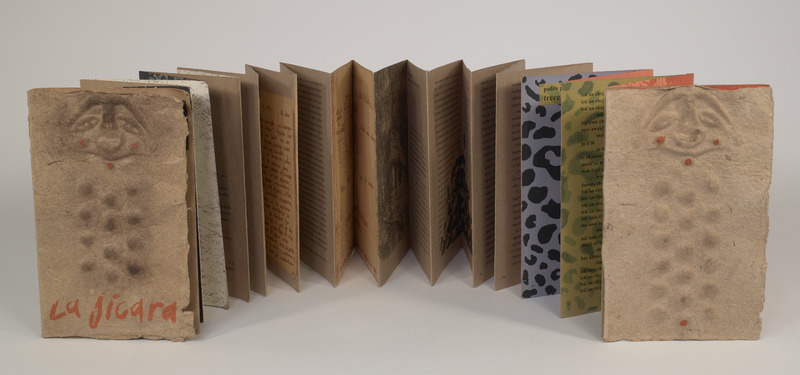

La jícaraAccordion fold format with bark paper sculpture covers attached; paged front to back and then back to front on verso. Poems and art by the Lacandon Indians of Mexico. "The cover or lining is made of recycled cardboard with maguey fiber in relief. The interiors are made of recycled paper and are all silkscreened, sheet by sheet. The binding is inspired by the ancient codices of our Indigenous Peoples. The entire magazine is handmade." - From the publisher, Taller Leñateros.

-

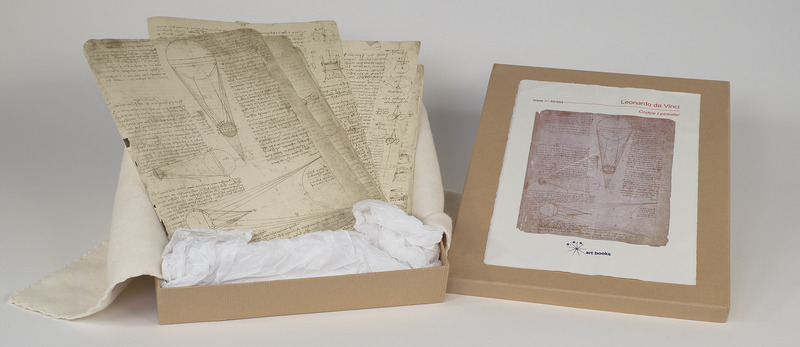

Codice LeicesterFacsimile of Leonardo's ms. treatise on water dynamics, composed in Milan between 1506 and 1510, and now in the collection of Bill Gates; Title from sheet mounted on box;Accompanied by editorial notes and colophon (2 sheets).

-

Self-portrait in a convex mirrorSelf-portrait in a convex mirror. In round silver brushed metal canister with convex mirrored dome. Poem in a round format, vinyl record with poet reading the poem. Essay, forward, and colophon. Eight original signed and numbered (86/175) limited edition prints. Copy 86 of an edition limited to 150 copies.

-

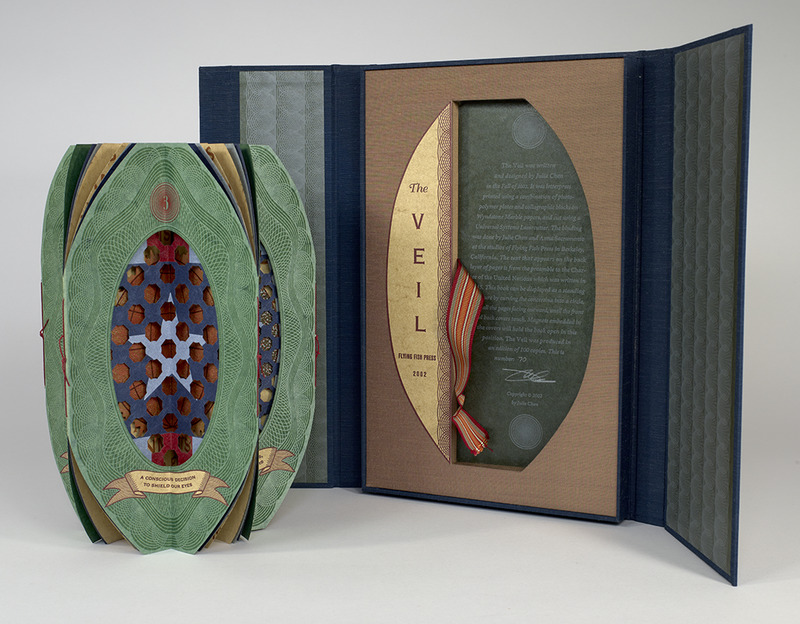

The VeilTitle from box.;" 'The Veil' was written and designed by Julie Chen in the fall of 2002. It was letterpress printed using a combination of photopolymer plates and collagraphic blocks on Wyndstone Marble papers, and cut using a Universal Systems Lasercutter. The binding was done by Julie Chen and Anna Sacramento at the studios of Flying Fish Press. The text that appears on the back layer of pages is from the preamble to the Charter of the United Nations which was written in 1945. --Box lining paper.";"Limited ed.of 100 copies, signed and numbered by the artist.";" This book can be displayed as a standing sculpture by curving the concertina into a circle, with all the pages facing outward, until the front and back covers touch. Magnets embedded in the covers will hold the book open in this position --Colophon.";"Book is a nested accordion structure. Each numbered opening has an image of the world seen through an increasingly dense veil of cut paper. Book is in a box (33 x 22 cm.) with magnetized closure.";"Library's copy 1 (Special Collect): Purchased. In container 34 cm."

-

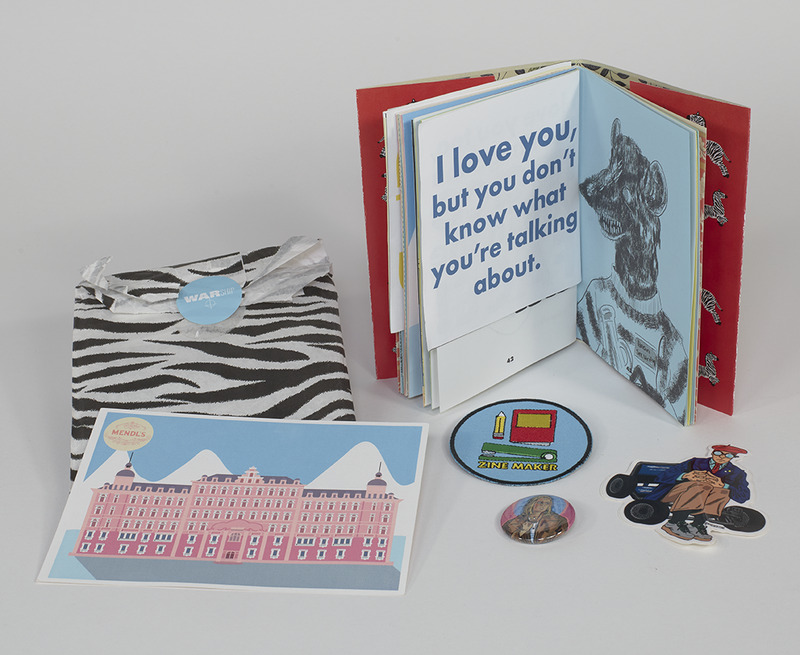

Wes Anderson issueThe Wes Anderson issue. Zine. Extras include a button, sticker, postcard, and zine maker patch!

-

David Bowie issue"Issue 4 of Warship is the David Bowie issue! This issue comes with 3 zines (totaling a bit over 100 pages), 4 stickers, 1 pin, 1 mini print, and comes in a sweet package! Zine features art and some writing on Bowie."

-

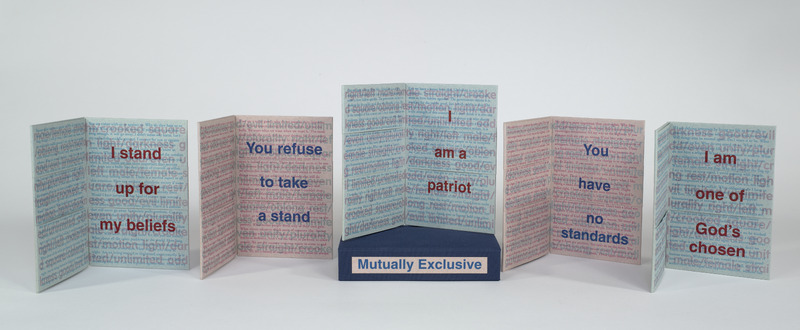

Mutually ExclusiveFive separate texts housed together in a separate cover; "An edition of 50 copies and two artist's proofs.";" This project was printed during the Sally R. Bishop artist's residency at the Center for Book Arts, New York, NY summer 2002 --Colophon.";"While provoked by the events of September 11, 2001, these five magic wallets address the cacophony of news reports, emotions and opinions (expert and otherwise) that follows in the wake of any major news event. Each wallet opens in either the left or right side, revealing one of two opposing statements.";"Library's copy 1 (Special Collect): Relocated from General Collection. In container."

-

La Relación - page 111Chapter Thirty-Six: How We Had Them Build Churches in That Land Chapter Thirty-Seven: What Happened When I Wanted to Leave Chapter Thirty-Eight: What Happened to the Others Who Went to the Indies

-

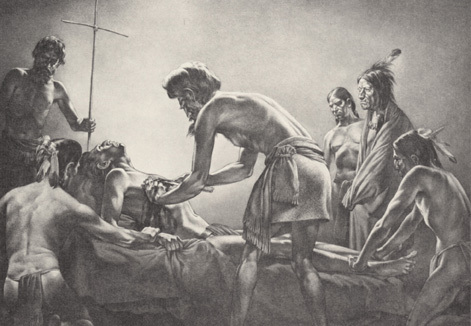

La Relación - page 110Chapter Eighteen: How He Told Esquivel's Story Chapter Nineteen: How the Indians Left Us Chapter Twenty: How We Escaped Chapter Twenty-One: How We Cured Some Sick People Chapter Twenty-Two: How They Brought Other Sick People to Us the Following Day Chapter Twenty-Three: How We Left after Having Eaten the Dogs Chapter Twenty-Four: About the Customs of the Indians of That Land Chapter Twenty-Five: How the Indians Are Skilled with a Weapon Chapter Twenty-Six: About the Peoples and Languages Chapter Twenty-Seven: How We Moved On and Were Welcomed Chapter Twenty-Eight: About Another New Custom Chapter Twenty-Nine: How They Stole from One Another Chapter Thirty: How the Custom of Welcoming Us Changed Chapter Thirty-One: How We Followed the Corn Route Chapter Thirty-Two: How They Gave Us Deer Hearts Chapter Thirty-Three: How We Saw Traces of Christians Chapter Thirty-Four: How I Sent for the Christians Chapter Thirty-Five: How the Mayor Received Us Well the Night We Arrived

-

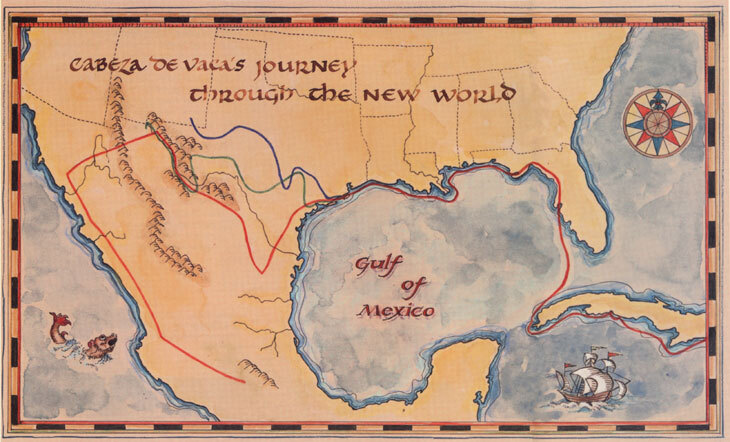

La Relación - page 109(In the original text, the table of contents appears at the end of the narrative.) Proem Chapter One: Which Tells When the Fleet Sailed, and of the Officers and People Who Went with It Chapter Two: How the Governor Came to the Port of Xagua and Brought a Pilot with Him Chapter Three: How We Arrived in Florida Chapter Four: How We Entered the Land Chapter Five: How the Governor Left the Ships Chapter Six: How We Entered Apalachee Chapter Seven: What the Land is Like Chapter Eight: How We Left Aute Chapter Nine: How We Left the Bay of Horses Chapter Ten: Of Our Skirmish with the Indians Chapter Eleven: What Happened to Lope de Oviedo with Some Indians Chapter Twelve: How the Indians Brought Us Food Chapter Thirteen: How We Found Out about Other Christians Chapter Fourteen: How Four Christians Departed Chapter Fifteen: What Happened to Us in the Village of Misfortune Chapter Sixteen: How Some Christians Left the Isle of Misfortune Chapter Seventeen: How the Indians Came and Brought Andrés Dorantes and Castillo and Estebanico

-

La Relación - page 108Since I have given an account of the ships, it will be fitting for me to tell who are the people whom our Lord was pleased to deliver from these afflictions and where in these kingdoms they are from. The first is Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, a native of Salamanca and son of Doctor Castillo and Doña Aldonza Maldonado. The second is Andrés Dorantes, son of Pablo Dorantes, a native of Béjar and resident of Gibraleón. The third is Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, son of Francisco de Vera and grandson of Pedro de Vera, who conquered the Canary Islands; his mother was named Doña Teresa Cabeza de Vaca, a native of Jerez de la Frontera. The fourth is named Estebanico; he is a black Arab and a native of Azamor. I give thanks.

-

La Relación - page 107we departed from them. The Governor had given them orders that they should then all assemble in the ships and continue their journey directly in the direction of Panuco, always sailing along the coast and looking for the harbor the best way they could, so that, once they had found it, they could anchor in it and wait for us. At the time they were assembling on the ships, they say that everyone there clearly heard that woman tell the other women, whose husbands were going inland and exposing themselves to such great danger, that they should not count on their returning and ought to look for someone else to marry as she intended to do. She did so, and she and the other women married and cohabited with the men who remained on the ships. After they departed from there, the ships sailed and followed their course, but did not find the harbor and turned back. Five leagues below where we had landed they found the harbor which stretched seven or eight leagues inland. It was the same one we had explored, where we had found the boxes from Castile mentioned above, containing the bodies of the men who were Christians. In this harbor and along this coast, the three ships, the brig and the other one that came from Havana went looking for us for nearly a year. Since they did not find us, they proceeded to New Spain. This harbor that we are talking about is the best in the world, stretching inland for a distance of seven or eight leagues. It is six fathoms deep at the entrance and five fathoms deep near land, with a fine sandy bottom. Within it there are no rough seas or strong storms, and it can accommodate many ships. There is a great quantity of fish in it. It is 100 leagues from Havana, a town of Christians in Cuba, on a north-south axis with this town. Here the winds are always fair and ships come and go from one place to the other in four days, with the wind on the quarter.

-

La Relación - page 106Since I have given an account of everything above concerning the voyage and the entrance into and the departure from the land until my return to these kingdoms, I wish likewise to furnish a record and account of what the people and the ships who remained there did. I have not mentioned this above because we knew nothing about them until we had come out. We found many of them in New Spain and others here in Castile. From these people we learned what happened, how it happened and how things ended. We left the three ships-because the other one had already been lost on the breakers-which remained at great risk, with little food and up to one hundred persons on board, among them ten married women. One of them had told the Governor many things that happened on the voyage before they happened. When he wanted to enter the land, she told him not to, because she believed that none of those who went with him would leave that land. She believed that if anyone should get out, God would perform very great miracles for him, but she believed that few or none would escape. The Govemor then answered her that he and all those who were penetrating the country with him were going to fight and conquer many very strange lands and peoples. He said that he was very sure that in conquering them many would die, but that the survivors would be fortunate and would be very rich, since he had heard that there were many riches in that land. The Govemor went further and asked her to tell him who had told her the things she had said about the past and the future. She replied that in Castile a Moorish woman from Hornachos had told her. She had told us this before we left Castile, and the entire voyage went the way she predicted. After the Governor left Carvallo, a native of Cuenca de Huete, as his lieutenant and captain of all the ships and people that he left there,

-

La Relación - page 105reached the galleon and the whole fleet saw that we were approaching them, they prepared for battle and came upon us, certain that we were French. When they were near, we hailed them. They discovered that we were friendly and realized that they had been deceived by the escaped privateer, who said that we were French and part of their convoy. So they sent four caravels after him. When the galleon approached us after we had saluted them, Captain Diego de Silveira asked us where we were coming from and what cargo we were carrying. We replied that we were coming from New Spain and carried silver and gold. He asked us how much, and the sailing master responded that we were taking about 300,000 castellanos. The captain replied, "By my faith, you're very rich, but you've got a very poor vessel and very poor artillery. That renegade French dog, the son of a bitch, lost a tasty morsel, by God! Now since you've escaped him, follow me and don't separate yourselves from me, because with God's help I'll take you to Castile." Shortly thereafter the caravels that had followed the Frenchman returned, since It seemed to them that he was going too fast. Furthermore, they did not want to leave the fleet, which was escorting three ships loaded with spices. So we arrived at the island of Terceira, where we rested for two weeks, taking on supplies and waiting for another ship that was coming from India with its cargo and was part of the convoy along with the three ships that were being escorted by the fleet. At the end of the two weeks, we left there with the fleet and reached the port of Lisbon on the ninth of August, eve of St. Lawrence's day, in the year 1537. Because what I say above in this account is the truth, I sign it with my name, Cabeza de Vaca. The account from which this was taken was signed with his name and bore his coat of arms. CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT What Happened to the Others Who Went to the Indies

-

La Relación - page 104that we would encounter Frenchmen, who several days earlier had captured three of our ships. When we arrived at the island of Bermuda, a storm overtook us, of the sort that often overtakes all who pass through there, according to those who frequently sail that area. All night long we feared we were lost. It pleased God for the storm to end in the morning, and we continued our voyage. Twenty-nine days after our departure from Havana, we had sailed 1, 100 leagues, the distance given from there to the settlement of the Azores. The following day, passing the island named Corvo, we met a French ship. At noon she began to pursue us, hauling with her a caravel she had captured from the Portuguese, and gave us chase. That afternoon we saw another nine sails, but they were so far away that we were unable to tell if they were Portuguese or if they belonged with those who were pursuing us. At nightfall the French vessel was a cannon-shot away from our ship. After dark we took another course to elude her. Since she was so close to us, they saw us and fired towards us; this happened three or four times. They could have captured us had they wanted to, but they were leaving it for morning. It pleased God that in the morning the French ship and ours were close together and surrounded by the nine sails I said I had seen the previous afternoon. We recognized that they were from the Portuguese navy, and I thanked God for having been able to escape hardships on land and dangers on the sea. Once she realized that it was the Portuguese navy, the French vessel released the caravel she had captured, which had a cargo of blacks. The French ship had taken the Portuguese caravel along so that we would think that they were Portuguese and wait for them. When the French released the Portuguese vessel, they told her sailing master and pilot that we were French and part of their convoy. When they said this they put out sixty oars and fled by oar and by sail so swiftly it was unbelievable. The caravel that she released went to the galleon and told the captain that our ship and the other one were French. When our ship

-

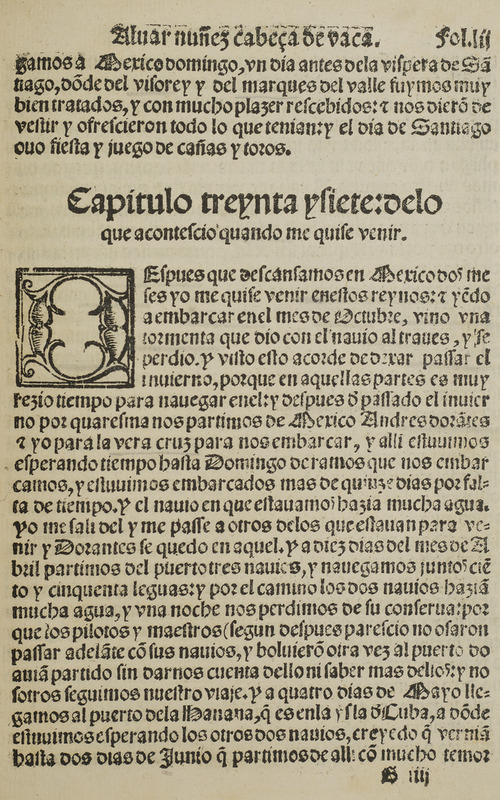

La Relación - page 103We arrived in Mexico City on a Sunday, one day before the eve of St. James' day. There the Viceroy' and the Marqués del Valle treated us very well and welcomed us very graciously. They gave us clothing and offered us everything they had. On St. James' day there were festivities with tournaments and bullfights. CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN What Happened When I Wanted to Leave After we rested in Mexico City for two months, I wanted to return to these kingdoms. As the ship was about to set sail in October, a storm came and grounded the ship, and it was lost. Seeing this, I decided to wait until winter was over, since it is a season of rough weather for sailing. During Lent, when winter had passed, Andrés Dorantes and I left Mexico City for Veracruz to board our ship. We waited there until Palm Sunday, when we boarded. We remained on board more than two weeks waiting for the wind. The ship we were on was taking on a great deal of water. I left it and went to others that were about to sail, but Dorantes remained aboard that ship. On the tenth of April three ships sailed out of the port, and we traveled together for 150 leagues. On the way, two ships were taking on a lot of water. One night we got lost from this convoy because their pilots and sailing masters, as it later seemed, did not dare continue onward with their ships and returned to the port from which they had sailed. We did not notice this or have any more news of them and continued our voyage. On the fourth of May we arrived in the port of Havana, which is on the island of Cuba, where we waited for the two other ships until the second of June, thinking they would come. Then we left there, greatly fearing

-

La Relación - page 102that the Indians had come out to greet them with crosses in their hands and had taken them to their houses and given them part of what they had. They slept with the Indians there that night. Stunned by this new manner, and because the Indians told them that their security was guaranteed, Alcaraz ordered that they not be harmed. Then the Christians departed. May it be God our Lord's will, through his infinite mercy, that in Your Majesty's lifetime and under your dominion and lordship, these peoples may come to be truly and quite willingly subject to the true Lord who created and redeemed them. We are certain that this will be so and that Your Majesty will be the one to carry it out. This will not be so difficult to achieve because throughout the two thousand leagues that we traveled overland and by boat on the sea, and during the ten months that we constantly traveled the land after we were out of captivity, we did not find any sacrifices or idolatry. During this time we traveled across from one sea to the other, and as far as we could carefully determine, the land may be about two hundred leagues across at its widest. We understand that on the southern coast there are pearls and much wealth and that the best and richest things are near that coast. We remained in the municipality of San Miguel until May 15th. The reason we stayed such a long time was that the city of Compostela, where Governor Nuño de Guzman resided, was one hundred leagues away, and the entire stretch is desolate and filled with enemies. Some men had to go with us, including twenty horsemen who accompanied us for forty leagues. From that point onward, six Christians who had five hundred enslaved Indians with them, went with us. When we arrived in Compostela, the Governor received us very well. He gave us some of his clothing, which I could not wear for many days, and we were able to sleep only on the floor. Ten or twelve days later we set out for Mexico City. All along the way we were treated well by Christians. Many of them would come out to the roads to see us, and they thanked God for having delivered us from so many perils.

-

La Relación - page 101and feed them what they had. This way the Christians would not harm them; instead, they would be their friends. They said they would do what we told them to do. The Captain gave them blankets and treated them very well. So they returned, taking with them the two who were captives and had gone as messengers. This happened in the presence of a notary who was there, along with many other witnesses. CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX How We Had Them Build Churches in That Land After the Indians returned, all the people of that province who were friends of the Christians came to see us when they heard news of us, and brought us beads and feathers. We told them to build churches and place crosses on them, which they had not yet done. We had them bring the children of the principal chiefs and baptized them. Then the Captain vowed to God that he would not raid nor allow anyone to raid or to take slaves in the land or from the people to whom we had guaranteed safety, and that he would keep and carry this out until Your Majesty and Governor Nuño de Guzmán or the Viceroy in your name decreed what would be of greatest service to God and Your Majesty. After the children were baptized, we departed for the municipality of San Miguel, where, upon our arrival, Indians came to tell us that many people were coming down from the mountains, settling in the plain, building churches and crosses and doing everything we had told them to do. Every day we had news on how this was increasingly being done. After we had been there two weeks, Alcaraz returned with the Christians who had been on that raid. They told the Captain how the Indians had come down from the mountains and had settled in the plain, and how they had found that formerly empty and deserted villages now had many people in them. They said

-

La Relación - page 100repay and reward good people and condemn bad people to eternal punishment with fire. We told them to say that when good people died, God took them to heaven, where no one ever died or was hungry or cold or thirsty or in need of anything, but instead experienced the greatest bliss imaginable; and that in the case of those people who refused to believe him or obey his commandments, God would cast them under the earth in the company of demons, into a great fire that would never end and would torment them forever; and that, besides this, if they wanted to be Christians and serve God the way we told them to, the Christians would consider them brothers and treat them very well. And we would tell the Christians not to harm them nor remove them from their lands, but instead to be their good friends. But if the Indians refused to do this, the Christians would treat them very badly and take them to other lands as slaves. The Indians replied to the interpreter that they would be very good Christians and they would serve God. When they were asked what they worshipped and sacrificed and whom they petitioned for water for their cornfields and health for themselves, they replied that it was a man who was in heaven. We asked them his name and they told us he was named Aguar, and that they believed that he had created the whole world and everything in it. We asked them how they knew this and they said their fathers and grandfathers had told them so, for they had known about this for a long time, and they knew that water and all good things were sent by him. We told them that we called the man they were describing God, and that they should also call him God and serve him and worship him as we had told them to do, and that things would turn out very well for them. They replied that they understood everything very well and would do so. We ordered them to come down from the mountains in peace and feel safe to populate the land and build their houses. Among their houses we told them to build one for God and to place at the entrance a cross like the one we had, and to greet arriving Christians with crosses in their hands and not with bows and arrows, and to take them to their houses

-

La Relación - page 99and wasted and the Indians were hiding and in flight through the woods, not wanting to settle in their villages. He wanted us to call them and order them in Your Majesty's name to return and settle the plain and cultivate the soil. We thought this would be very difficult to carry out because we had not brought any of our Indians with us nor any of those who usually accompanied us and understood these matters. At last we sent for this purpose two of the Indians they had brought as captives, who were of the same people as the Indians of that land. These two were with the Christians when we first reached them, and they saw the people that accompanied us and learned from them the great authority and dominion we had throughout all those lands, the wonders we had worked, the sick people we had healed, as well as many other things. We sent other Indians from the village with these and told them to go together to call the Indians who were up in the mountains and the people from the Petaán River, where we had found the Christians. We told them to tell the Indians to come to us because we wanted to speak to them. To insure that they would be safe and the others would come, we gave them one of the large gourds that we carried in our hands, our chief insignia and a sign of our high status. They left with it and traveled for seven days. At the end of this period, they returned, bringing three chiefs of the people who were up in the mountains. Each chief had fifteen men with him. They also brought us beads, turquoises and plumes. The messengers told us that they had not found the natives of the river where we had met the Christians, because the Christians had once again caused them to flee into the mountains. Melchor Díaz told the interpreter to speak to those Indians on our behalf, telling them that we came on behalf of God, who is in heaven, and that we had gone through the world for many years telling all the people we met to believe in God and serve him, because he was the lord of everything in the world and would

-

La Relación - page 98and when we thought we had secured it, quite the opposite happened, since the Christians had planned to attack the Indians whom we had reassured and sent in peace. They carried out their plan. They took us through the wilderness for two days without water, lost and without a trail. We thought we would all die of thirst and, in fact, seven men did. Many of the Indian allies accompanying the Christians could not reach the place where we found water that night until the following day at noon. We traveled with them for twenty-five leagues, more or less, and arrived at a pacified Indian village. The Justice who was taking us left us there and went ahead three leagues to a town called Culiacán, where Melchor Díaz, the Mayor and Captain of that province, lived. CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE How the Mayor Received Us Well the Night We Arrived When the Mayor was informed of our departure and arrival, he set out that night and came to where we were. He wept a great deal with us, giving praise to God our Lord for having shown us such great mercy. He conversed with us and treated us very well, and on his own behalf and that of Governor Nuño de Guzmán he offered us everything he had or could do and regretted the poor reception and treatment Alcaraz and the others had given us. We were certain that, if he had been there, he would have prevented what was done to us and to the Indians. We spent the night there and departed the following day. The Mayor entreated us to remain there, saying that we would render great service to God and to Your Majesty by doing so, since the land was abandoned

-

La Relación - page 97while the sole purpose of the others was to steal everything they found, never giving anything to anybody. In this manner they talked about us, praising everything about us and saying the contrary about the others. They replied this way to the Christians' interpreter and told the others through an interpreter they had among themselves, whom we understood. We properly call the people who speak that language the Primahaitu, which is like saying the Basques. We found that this language was used among them and no other was used in the 400-league stretch that we traveled. The Indians could not be persuaded to believe that we were the same as the other Christians. We had great difficulty and had to insist in order to persuade the Indians to return to their homes. We ordered them to make themselves secure and settle their villages and plant and till the soil, which was already overgrown because it had been abandoned. This land is without a doubt the best in all the Indies, the most fertile and abundant in food. They plant crops three times a year. They have many fruits and beautiful rivers and many other very good bodies of water. There is great evidence and signs of gold and silver deposits. The people are very congenial: they serve Christians-the ones who are friendly-quite willingly. They are well built, much more so than the Indians of Mexico. This truly is a land that lacks nothing to be very good. When the Indians departed they told us that they would do what we said and would settle their villages if the Christians would allow them. I want to make it quite clear and certain that if they should not do so, the Christians will be to blame. After we sent the Indians away in peace, thanking them for the trouble they had taken with us, the Christians sent us under guard to a certain Justice named Cebreros and two other men with him, who took us through wilderness and uninhabited areas to keep us from talking to Indians and so that we could not see or understand what they really did to the Indians. From this, one can see how easily the ideas of men are thwarted, for we wanted freedom for the Indians,

-

La Relación - page 96although this was not necessary since they always took care to bring us everything they could. We sent messengers to call them, and six hundred people came, bringing all the corn they had in pots sealed with clay, in which they had buried it to hide it. They also brought us everything else they had. We took only the food and gave the rest to the Christians to divide among themselves. After this we had many great quarrels with the Christians because they wanted to enslave the Indians we had brought with us. We were so angry that when we departed we left many Turkish-style bows that we were carrying, as well as many pouches and arrows, among them the five with the emeralds, which we lost because we forgot about them. We gave the Christians many buffalo-hide blankets and other things we had. We had great difficulty in persuading the Indians to return to their homes, to feel secure and to plant com. They wanted only to accompany us until they handed us over to other Indians, as was their custom. They feared that if they returned without doing this they would die, but they did not fear the Christians or their lances when they were with us. The Christians did not like this and had their interpreter tell them that we were the same kind of people they were, who had gotten lost a long time before, and that we were people of little luck and valor. They said that they were the lords of that land, and that the Indians should obey and serve them, but the Indians believed very little or nothing of what they were saying. Speaking among themselves, they said instead that the Christians were lying, because we had come from the East and they had come from the West; that we healed the sick and they killed the healthy; that we were naked and barefooted and they were dressed and on horseback, with lances; that we coveted nothing but instead gave away everything that was given to us and kept none of it,

-

La Relación - page 95They looked at me for a long time, so astonished that they were not able to speak or ask me questions. I told them to take me to their captain. So we went to a place half a league from there, where Diego de Alcaraz, their captain, was. After I spoke to him, he told me that he had quite a problem because he had not been able to capture Indians for many days. He did not know where to turn, because he and his men were beginning to suffer want and hunger. I told him that I had left Dorantes and Castillo behind, ten leagues from there, with many people who had brought us there. Then he sent three horsemen and fifty of the Indians they were bringing along, and the black man returned with them to guide them. I remained there and asked them to witness the month, day and year that I had arrived there, and the manner in which I arrived, and they did so. There are thirty leagues from this river to the Christian town called San Miguel, under the jurisdiction of the province called New Galicia. CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR How I Sent for the Christians Five days later Andrés Dorantes and Alonso del Castillo arrived with those who had gone for them. They brought along more than six hundred persons from that village, whom the Christians had forced to go up the mountain, where they were hiding. Those who had accompanied us to that place had taken the people out of the mountains and had handed them over to the Christians, and had sent away all the other people they had brought to that point. They came to where I was and Alcaraz asked me to send for the people from the villages on the riverbanks, who were hiding in the mountains in that area. He wanted me to ask them to bring us food,

-

La Relación - page 94twelve leagues. Throughout the mountainous areas of this entire land we saw many signs of gold and antimony, iron, copper and other metals. The area in which the permanent settlements are located is hot, so much so that even in January the weather is very hot. From there towards the south of that land- which is uninhabited all the way to the North Sea-the country is very wretched and poor, and we suffered from incredibly great hunger. The people who live there are terribly cruel and of very evil inclinations and customs. The Indians in the permanent settlements and the ones further back pay no attention at all to gold and silver, nor do they find them useful. CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE How We Saw Traces of Christians After we clearly saw traces of Christians and realized that we were so near them, we gave great thanks to God our Lord for willing that we should be brought out of our sad and wretched captivity. Anyone considering the length of time we spent in that land and the dangers and afflictions we suffered can imagine the delight we felt. That night I asked one of my companions to go after the Christians, who were going to the area of the country where we had assured the people of protection, which was a three- day journey. They reacted negatively to this idea, excusing themselves because it would be difficult and they were tired, although any one of them could have done it more easily because they were younger and stronger. When I saw their unwillingness, the following morning I took the black man and eleven Indians and, following the trail of the Christians, went by three places where they had slept. That day I traveled ten leagues. The following morning I caught up with four Christians on horseback who were quite perturbed to see me so strangely dressed and in the company of Indians.

-

La Relación - page 93very difficult ascent. There we found many people gathered together for fear of the Christians. They received us very well and gave us everything they had. They gave us two thousand loads of com, which we gave to those miserable, hungry people who had taken us there. The following day we dispatched four messengers from there, as was our custom, to call and convene all the people they could to a village three days' journey from there. After doing this, we set out the following day with all the people there. Along the way we found signs and traces of the places where Christians had spent the night. At midday we came upon our messengers, who told us they had found no people because they were all hiding in the mountains, fleeing so that the Christians would not kill them or enslave them. They said that the previous night they had seen Christians. The Indians had hidden behind some trees to see what the Christians were doing and they saw that they were taking many Indians in chains. The Indians who had come with us were greatly upset by this, and some of them turned back to give the warning throughout the land that Christians were coming. Many more would have done the same if we had not told them not to do it and not to be afraid. They were greatly reassured and relieved by this. Indians who lived one hundred leagues away then came with us there since we could not persuade them to return to their homes. To reassure them we slept there that night. The next day we traveled on and slept on the way. The following day, the Indians we had sent ahead as messengers led us to where they had seen the Christians. We arrived there at the hour of vespers and clearly saw that they had told the truth. We noticed that horsemen had been there because we saw the stakes where the horses had been tethered. From this place, called the Petutan River, to the river reached by Diego de Guzmán, where we first heard of Christians, there may be eighty leagues; from there to the village where we were caught in the rains, twelve leagues; and from that village to the South Sea,

-

La Relación - page 92or remove them from their lands or harm them in any other way. This pleased them very much. We traveled far and found the entire country empty because the people who lived there were fleeing into the mountains, not daring to work the fields or plant crops for fear of the Christians. It was very pitiful for us to see such a fertile and beautiful land, filled with water and rivers, with abandoned and burned villages, and to see that the people, who were weakened and sick, all had to flee and hide. Since they could not plant crops, they were very hungry and had to survive by eating tree bark and roots. We too had to endure this hunger all along this route, since they were so miserable that they looked as though they were about to die and could hardly be expected to provide much for us. They brought us blankets that they had hidden from the Christians and gave them to us. They told us how on different occasions the Christians had raided their land and had destroyed and burned villages and carried off half the men and all the women and children. Those who had been able to escape from their clutches were fleeing. We saw that they were so terrorized that they did not dare to stay in one place. They could not plant or cultivate their fields. They were determined to die and thought this would be better than to wait for such cruel treatment as they had already received. They were very pleased to see us, but we feared that when we reached the Indians who lived on the border with Christians and were at war with them, those people would mistreat us and make us pay for what the Christians were doing to them. But since God our Lord was pleased to bring us to them, they began to be in awe of us and revere us as the previous people had done, and even more so, which amazed us. By this, one can clearly recognize that all these people, in order to be attracted to becoming Christians and subjects of your Imperial Majesty, need to be treated well; this is a very sure way to accomplish this; indeed, there is no other way. These people took us to a village on the crest of a mountain range, which is reached by a

-

La Relación - page 91There are three kinds of deer there; one kind is as large as the yearling steers of Castile. They have permanent dwellings called buhios and poison from a tree the size of an apple tree. All that is necessary is to pick the fruit and rub it on an arrow. If there is no fruit, they break a branch and do the same with the milky sap. There are many of these trees, which are so poisonous that if the leaves are crushed and washed in water, any deer or other animals that drink the water later burst. We stayed in this village three days. A day's Journey from there was another village. There it rained so much that we could not cross a river, that had risen very much; so we had to wait two weeks. At this time Castillo saw a buckle from a sword belt around an Indian's neck, with a horseshoe nail sewn to it. Castillo took it away from him and we asked the Indian what it was. They replied that it had come from heaven. We questioned them further, asking them who had brought it from there. They told us that some bearded men like us, with horses, lances and swords, had come there from heaven and gone to that river and had speared two Indians. Trying very hard to act disinterested, we asked them what had happened to those men. They replied that the men went down to the sea, put their lances underwater and then went under the water themselves. Then they saw them go over the water towards the sunset. We gave great thanks to God our Lord when we heard this, since we doubted we would ever have news of Christians. On the other hand, we felt sad and bewildered, thinking that those men might have been only explorers who arrived by sea. But since we had such sure evidence about them, we finally decided to go faster on our way, where we heard more news about Christians. We told the people we were looking for the Christians so that we could tell them not to kill them or take them as slaves

-

La Relación - page 90Throughout these lands those who were at war with one another made peace to come to greet us and give us all they owned. In this way we left the whole country in peace. We told them in sign language which they understood that in heaven there was a man whom we called God, who had created heaven and earth, and that we worshipped him and considered him our Lord and did everything that he commanded. We said that all good things came from his hand and that if they did the same, things would go very well for them. We found that they were so well disposed for it that, if we could have communicated perfectly in a common language, we could have converted them all to Christianity. We tried to communicate these things to them the best we could. From then on at sunrise, with a great shout they would stretch their hands towards heaven and run them over their entire bodies. They did the same thing at sunset. They are affable and resourceful people and capable of pursuing anything. CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO How They Gave Us the Deer Hearts In the village where they gave us the emeralds, they gave Dorantes more than six hundred opened deer hearts which they store in abundance for food. For this reason we called the place the Village of Hearts. Through it one enters many provinces that are on the South Sea. Anyone who does not set out for the sea through this place will perish because there is no corn along the coast. There the people eat ground rushes, straw and fish caught in the sea in rafts, for they have no canoes. The women cover their private parts with grass and straw. These people are very shy and sad. We believe that near the coast on the way that we took to those villages there are more than a thousand leagues of inhabited land, with a great deal of food because they plant beans and corn three times a year.

-

La Relación - page 89gotten them. They told me that they brought them from some very high mountains to the North, where they traded them for plumes and parrot feathers. They said that there were large towns and very large dwellings there. Among these people we saw women treated more decently than in any other place we had seen in the Indies. They wear knee-length cotton shirts with short sleeves and over this, floor-length skirts of scraped deerskin. They keep them looking very nice by washing them with soap made from certain roots, which cleans them very well. They are open in the front and tied with straps. They also wear shoes. All these people came to us to be touched and blessed. They were so insistent that it was very difficult for us to deal with this. Everyone, sick or healthy, wanted to be blessed. It often happened that women who were traveling with us gave birth along the way. Once the child was born they would bring it to us to be touched and blessed. They always accompanied us until they turned us over to other people. All these people were certain that we had come from heaven. While we were with these people, we would travel all day without eating until nighttime. They were astonished to see how little we ate. They never saw us get tired, and really we were so used to hardship that we did not feel tired. We enjoyed a great deal of authority and dignity among them, and to maintain this we spoke very little to them. The black man always spoke to them, ascertaining which way to go and what villages we would find and all the other things we wanted to know. We encountered a great number and variety of languages; God Our Lord favored us in all these cases, because we were able to communicate always. We would ask in sign language and be answered the same way, as if we spoke their language and they spoke ours. We knew six languages, but they were not useful everywhere, since we found more than a thousand differences.

-

La Relación - page 88we would find what we wanted. So we made our way and crossed the entire country until we came to the South Sea. Their stories of great hunger were not enough to frighten us and keep us from doing this, although we did suffer greatly from hunger for seventeen days, as they had said we would. All along the way upriver people gave us many buffalo-skin blankets. We did not eat that fruit [chacan]; our only food each day was a handful of deer fat which we always tried to keep for such times of need. And so we journeyed for seventeen days, at the end of which we crossed the river and traveled for seventeen more. At sunset, on plains between some very tall mountains, we found some people who eat nothing but powdered straw for a third of the year. Since it was that season of the year, we had to eat it too. At the end of our journey we found a permanent settlement where there was abundant com. The people gave us a large quantity of it and of cornmeal, squash, beans and cotton blankets. We loaded the people who had led us there with everything and they departed the happiest people in the world. We gave great thanks to God our Lord for having led us there where we had found so much food. Some of these dwellings were made of earth and the others made of reed mats. From here we traveled over a hundred leagues, always finding permanent settlements and much corn and beans to eat. The people gave us many deer and cotton blankets better than the ones from New Spain. They also gave us many beads and a kind of coral from the South Sea, along with many very fine turquoises from the North. In sum, they gave us everything they had. They gave me five emeralds made into arrowheads. They use these arrows for their areítos and dances. Since they seemed very fine to me, I asked them where they had

-

La Relación - page 87They also told us that as long as we went upriver we would encounter people who spoke their language but were their enemies. They said that these people would not have any food for us to eat, but that they would welcome us and give us many cotton blankets and hides and others things of theirs. Still they thought that under no circumstances should we go in that direction. We stayed with them for two days, wondering what to do and which would be the most suitable and beneficial way for us to go. They gave us beans and squash to eat. Since their way of cooking them is so novel, I want to tell about it here, so that people may see and know how diverse and strange human ingenuity and industriousness are. They have no pots; so to cook what they want to eat, they fill a large pumpkin halfway with water. They heat many stones in a fire, and when the stones are hot, they grab them with wooden tongs and put them in the water inside the pumpkin, until the water boils with the heat of the stones. Then they place in the water whatever they want to cook. The whole time they remove stones and add other hot stones to bring the water to a boil and cook whatever they wish. This is their method of cooking. CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE How We Followed the Corn Route After spending two days there, we decided to go look for corn. We did not want to follow the buffalo trails towards the North and go out of our way, since we were always sure that by heading west

-

La Relación - page 86had done. Instead they remained in their houses and had others ready for us. They were all seated and had their faces turned toward the wall, their heads lowered and their hair in front of their eyes, with all their possessions piled in the middle of the room. From here on, they began to give us many animal skin blankets, and gave us everything they had. These people had the best physiques of any we saw. They were the liveliest and most skillful, and the ones who understood and answered our questions best. We called them the Cow People, because the greatest number of buffalo die near there, and for fifty leagues up the river they kill many buffalo. These people walk around totally nude, like the first ones we encountered. The women cover themselves with deerskins, as do a few men, especially those who are too old for battle. The country is fairly well populated. We asked them why they did not plant corn. They told us it was because they did not want to lose what they planted, since the rains had not come for two years in a row. The weather was so dry that they had lost their corn to moles. They said they would not try planting again until after a lot of rain. The asked us to tell the sky to give rain and beg it to do so, and we promised them we would do that. We wanted to know where their com had come from. They told us that it had come from the direction of the setting sun and that there was corn throughout that land, but that the nearest was in that direction. We asked them to tell us how to go there, since they did not want to go themselves. They told us to go up along that river towards the North, saying that for seventeen days the only food we would find is a fruit called chacan, which they crush between stones, and even then it is too bitter and dry to eat. They proved this by showing us some, which we could not eat.

-

La Relación - page 85saying that they had found very few people, since all of them had gone to where the buffalo were, since this was the season for them. We told those who had been sick to remain and those who were well to go with us. Two days' journey from there, those same two women would go with two of us to bring out people to the trail to receive us. So the next morning all the fittest departed with us. We stopped after journeying for three days. The following day Alonso del Castillo set out with Estebanico the black man, taking the two women as guides. The one who was a captive took them to a river that ran through some mountains, to a village where her father lived. Here we saw the first houses that really looked like houses. Castillo and Estebanico went there. Having spoken to the Indians, Castillo returned after three days to where he had left us, bringing five or six of those Indians. He said that he saw people's dwellings and permanent settlements, and that those people ate beans and squash, and that he had seen corn. This made us the happiest people in the world, and we thanked our Lord heartily for it. He said that the black man would return with all the people from the houses to wait near there along the way. For this reason we departed. A league and a half away, we came upon the black man and the people who were coming to receive us. They gave us beans and many squashes to eat and gourds for carrying water, and buffalo skin blankets and other things. Since these people and the ones who had come with us were enemies and did not get along, we left the latter, giving them what we had been given, and went with these new people. Six leagues from there, as night was falling, we reached their houses, where they had a great celebration with us. We stayed there for a day, and the following day took them with us to another permanent settlement where they ate the same things as these people. From that point on there was a new custom. Those who knew we were coming would not come out to the trails to welcome us as the others

-

La Relación - page 84a strange thing happened: that very day many of them became sick and the following day eight men died. Wherever this was known throughout the land, people were so afraid of us that it seemed that they were going to die of fear when they saw us. They begged us not to be angry or to wish any more of them dead, since they were certain that we killed them by willing it. We were truly and completely grieved by this, not only because we were seeing some of them die, but also because we were afraid they would all die or, acting out of fear, would leave us alone and all the peoples ahead would do the same, seeing what had happened to these people. We prayed to God our Lord for his help, and all sick began to get well. We saw a very amazing thing: the parents and siblings and wives of those who later died were very grieved to see them ailing, but after they died the relatives showed no feelings. We did not see them weep or speak to one another nor show any emotion. They did not dare to approach their dead until we told them to carry them away for burial. In the two weeks that we were with them, we did not see people speaking to one another. We did not even see a child laugh or cry; in fact, one who cried was taken far away from there and scratched with sharp mouse teeth from the shoulders to nearly the bottom of the legs. When I saw this cruel treatment I was angered by it, and asked them why they did it. They replied that they did it to punish the child because it had cried in my presence. They instilled these fears in all the others who joined them to see us. They did this so that the new people would give us everything they had, since they knew that we would give it all to them and keep none of it. These were the most obedient people we found in this land, having the best temperament. They generally are very handsome. By the time the sick people felt well, we had been there three days, and the women we had sent returned,

-

La Relación - page 83same people took us to some plains near the mountains, where other people were coming from a great distance to receive us. They welcomed us as the others had done, giving so much wealth to those who had come with us that they had to leave half of it because they could not carry It. We told the Indians who had given it to take the remainder back so that it would not remain there and go to waste. They replied that they would in no way do so, because it was not their custom to take back what they had already given away. So they did not value it and left it there, losing it all. We told these people that we wanted to go towards the sunset. They replied that in that direction there were no people for a long distance, but we told them to send messengers to let them know we were coming. As best they could, they declined to do this, because those people were their enemies-and they did not want us to go to them. But they did not dare disobey; so they sent two women, one of their own and another whom they were holding captive, since women can negotiate even if a war is going on. We followed them, and stopped at a place we had agreed upon for meeting them. But they took five days and the Indians said that they must not have found any people. We told them to lead us north, but they answered the same, saying that the only people in that direction were far away and that there was neither food nor water. We nevertheless insisted and told them that we wanted to go in that direction, but they still declined as best they could. We became angry at this and I went out one night to sleep in the wilderness away from them. They soon went to where I was and spent the whole night fearful and without sleeping, talking to me and telling me how afraid they were, begging us not to be angry any more. They said they would take us wherever we wanted to go even if they knew they would die on the way. While we continued to pretend we were angry so that they would remain fearful,

-

La Relación - page 82they could get, because even if they were starving they would not eat anything unless we gave it to them. Going with these people we crossed a great river which flowed from the North. After crossing some plains thirty leagues wide, we saw many people in the distance coming to welcome us. And they came out to the path we were going, to take and greeted us in the same way the others had done. CHAPTER THIRTY How the Custom of Welcoming Us Changed From this point on, the custom of receiving changed with regard to looting, and the people who came out to the roads to bring us something were not robbed by those who were with us. After we had entered their homes, they offered us everything they had, including their dwellings. We would give all these things to their leaders for them to distribute. The people who had lost things always followed us, and the number of people wishing to make up their loss was growing larger. Their leaders told them to take care not to hide any of their belongings, saying that if we found out we might cause them all to die because the sun would tell us to do so. Their leaders made them so fearful that for the first few days that these people were with us they did nothing but tremble without daring to speak or to look up towards the sky. These people guided us through more than fifty leagues of uninhabited and rugged mountains. Since it was such dry country, there was no game in it, and for this reason we suffered a great deal of hunger. After this we crossed a very large river, with water up to our chests. From this point on many of the people we had with us began to suffer from the great hunger and hardship they had endured in those mountains, which were extremely barren and harsh. These

-

La Relación - page 81we could not deal with them. As we went through those valleys, they all went in a row, each one of them carrying a club three palms long. Whenever one of the many hares around there leaped up, so many people surrounded it and clubbed it that it was amazing thing to see. This way they made it go from one man to another. This seemed to me to be the best type of hunting imaginable, because sometimes the hares would come up to someone's hands. When we stopped at nightfall, they had given us so many hares that each of us carried eight or ten loads of them. We could not see those who had bows; they went separately through the mountains hunting deer, and at night they came bringing for each one of us five or six deer and birds and quail and other game. Everything those people found and killed they brought before us, not daring to take a bite even if they were starving, until we had blessed it. And the women brought many mats which they used to make lodges for us, each one of us having one for himself and all the people attached to him. When this was done, we would tell them to roast the deer and the hares and all that they had caught, and they did this very quickly in ovens they would make for this. We would take a little of everything and would give the rest to the leader of the people who had come with us, telling him to distribute it among them all. Each person would bring his portion to us so that we could breathe on it and make the sign of the cross on it; otherwise they would not dare eat it. Often three or four thousand people accompanied us, and it was very difficult for us to breathe on and bless each one's food and drink. They would come to ask our permission to do many other things, which indicates how we were inconvenienced by them. The women would bring us prickly pears and spiders and worms and whatever

-

La Relación - page 80and then they returned to us, continually running while coming and going. In this manner they brought us many things for our journey. Here they brought a man to me whom they said had been wounded by an arrow a long time before, in the right side of his back. They said that the arrowhead was over his heart. He said that it hurt a great deal and that it caused him to suffer all the time. I touched him and felt the arrowhead and noticed that it had gone through cartilage. With a knife that I had, I opened his chest through to that spot, and saw that the arrowhead had gone through and would be very difficult to remove. I cut further, stuck the point of the knife in, and at last removed it with great difficulty. It was very long. With a deer bone, I practiced my trade as a physician and gave him two stitches. After I had stitched, he was losing a lot of blood. I stopped the bleeding with hair scraped from an animal skin. When I removed the arrowhead they asked me for it and I gave it to them. The entire village came to see it and they sent it further inland so that the people there could see it. Because of this cure, they made many dances and festivities as is their custom. The following day I cut the stitches and the Indian was healed. The incision I had made looked only like one of the lines in the palm of one's hand, and he said that he felt no pain or suffering at all. And this cure gave us such standing throughout the land that they esteemed and valued us to their utmost capacity. We showed them the rattle, which we had brought. They told us that in the place from which it had come there were many sheets of that material buried and that they valued it very much and that there were settlements there. We believed that this was on the South Sea, which we always had been told was richer than the North Sea. We left these people and wandered among so many others and so many diverse languages that it is impossible to remember them all to tell about them. They always looted one another, and that way those who lost and those who gained were equally happy. So many people accompanied us that

-

La Relación - page 79when they think it is to their advantage. When we approached the dwellings, all the people came out to greet us with considerable pleasure and festivity. Two of their medicine men gave us, among other things, two gourds. From here on we began to carry the gourds with us, and added to our authority with this bit of ceremony, which is very important to them. Those who had accompanied us looted their lodges, but since there were many people in that village and there were only a few of them, they could not carry all that they took and had to leave more than half. From here we began penetrating the land for more than fifty leagues along the slope of the mountains. At the end our journey we found forty dwellings. Among the things the people there gave us was a thick rattle, large and made of copper, with a face on it. They let us know that they regarded it highly, and told us that they had gotten it from others who were their neighbors. When we asked them where the neighbors had gotten it, they said that they had brought it from the North, where there was much wealth, and it was greatly valued. We realized that wherever the object had come from there was smelting and metal casting. With this we departed the following day and crossed a mountain range seven leagues in length, where the rocks were iron slags. At nightfall we reached a large number of dwellings on the bank of a beautiful river. The inhabitants came out to welcome us carrying their children. They gave us many small bags of mica and powdered antimony. They rub this on their faces. They also gave us many beads and many buffalo-skin blankets and loaded all of us with everything they had. They eat prickly pears and pine nuts. In that land there are small pine trees, with cones the size of small eggs. Their seeds are better than the pine nuts from Castile because their husks are thinner. They grind them when they are green and make pellets out of them and eat them that way. If they are dry they grind them with husks and eat the powder. All those who greeted us there ran back to their lodges once they had touched us

-

La Relación - page 78a village of some twenty lodges, where they welcomed us weeping very sadly because they knew that wherever we had gone the people with us looted and robbed. When they saw that we were alone they lost their fear and gave us prickly pears and nothing else. We spent the night there and at dawn the Indians we had left the previous day came upon their lodges. Since they caught them off guard, they took everything they had without giving them an opportunity to hide anything, which caused them to weep a great deal. In order to console them, the robbers told them that we were children of the sun, that we had the power to heal the sick or to kill them, and many lies bigger than these, since they know best how to spin lies when they think it would be to their advantage to do so. They told them that they should treat us with much deference and take care not to anger us in any way. They also told them to give us everything they had and to take us to a place where there were many people, and to plunder and rob everything where they took us, for that was the custom. CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE How They Stole from One Another After having informed them and told them clearly what they should do, they returned and left us with those Indians, who, keeping in mind what the others had said, began to treat us with the same fear and reverence as the others. They took us on a three-day journey to a place where there were many people. Before we arrived, they sent word saying that we were coming, repeating everything about us that the other Indians had told them and adding much more, because all these Indians are great storytellers and big liars, especially

-

La Relación - page 77lived at the edge of the mountains. They said that there were many lodges and people there who would give us many things, but we did not want to go there because it was out of our way. We followed the flat land near the mountains, which we thought were not far from the coast. All the people of the coast are bad; so we thought it better to travel inland, because further inland the people are friendlier and treated us better. We thought we would certainly find a land that was more heavily populated and had more food. Furthermore, we did this so as to note the many particular things of that land, so that we could give an informative account of it if God our Lord should be pleased to lead one of us out and into a Christian land. When the Indians saw that we were determined not to go where they were leading us, they told us that there were no people there nor prickly pears or anything to eat where we wanted to travel. They asked us to stay there that day, which we did. Then they sent two Indians to look for people along the route we wanted to take. We left the following day, taking many of them with us. The women were carrying heavy loads of water, and our authority among them was so great that no one dared drink without our permission. Two leagues from there we encountered the Indians who had gone to look for people. They told us that they had found none and were sorry and asked us again to go through the mountains. We refused to do that and when they saw our determination they sadly took leave of us and returned downriver to their dwellings. We traveled upriver and a little while later we came across two women carrying loads. When they saw us, they stopped and unloaded and brought us some of what they were carrying, which was cornmeal. They told us that further along that river we would find dwellings and many prickly pears and some cornmeal. We said goodbye to them since they were going to the other Indians from whom we had come. We traveled until sunset and reached

-

La Relación - page 76we should not be saddened by it, because they were so glad to see us that they considered their belongings well spent. They said they would be repaid later on by others who were very rich. We had a great deal of difficulty all along the way because so many people were following us. We couldn't escape them even if we tried, because they were in a great hurry to reach us and touch us. They were so insistent about this that sometimes three hours would go by and still we could not make them leave us alone. The following day they brought us all the people of the village. Most of them were clouded in one eye and others totally blind because of the same cause, which astonished us. They are very well built people with fine features, whiter than any others we had seen. Here we began to see mountains, which seemed to come all the way from the North Sea. From the information the Indians gave us about this, we believe that they are fifteen leagues from the sea. We left with these Indians towards this mountain range. They led us through a place where their kinsmen lived, since they wanted to take us only to places where their kinfolks lived. They did not want their enemies to profit even from seeing us. When we arrived, the people who led us there looted the others. Since they were familiar with the custom, they had hidden some things before we arrived. After they had welcomed us with much festivity and rejoicing, they retrieved what they had hidden and came to present it to us. The items were beads, red ochre and some small bags of silver. Following the custom, we gave it to the Indians who had come with us. Once they had given it to us, they began their dances and festivities and sent for others from a neighboring village to come see us. That afternoon they all came, bringing us beads and bows and other things that we distributed. The following day when we wanted to leave, everybody wanted to take us to where some friends of theirs

-

La Relación - page 75with the others with whom we had stayed. After this, they gave many arrows to the women from the other village who had accompanied their own women. We departed the following day, and all the people of the village went with us. When we reached other Indians, we were welcomed as we had been before. They gave us part of what they had and gave us the deer they had killed that day. Among these we noticed a new custom. They took the bow and arrows and shoes and beads-if they had any-of those who came for healing. After taking the items, they brought the people to us for healing. Once we had performed the healing, they went away very happy, saying they were well. So we left those Indians and went to others who received us very well. They brought their sick people to us, who said they were well after we made the sign of the cross on them. Even those who did not get well thought we could heal them, and when they heard what the others we healed were saying, they danced and rejoiced such that we could not sleep. CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT About Another New Custom Having left these people, we went to another large group of lodges. Here another new custom began. After they received us well, the people who had gone with us began to do wrong to them, taking their possessions and looting their homes without leaving them anything. We were very sorry to see this ill treatment of those who had welcomed us and we also feared that this might cause some altercation or uproar among them. But since we had no way to prevent it nor to punish those who were doing it, we had to suffer it until we had greater authority among them. Even the Indians who had lost their belongings noticed our sorrow and tried to console us, saying that

-